List of Saint Patrick's crosses

A variety of crosses, both designs and physical objects, have been associated with Saint Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland. Traditionally, the cross pattée has been associated with him, but in more recent times, the Saint Patrick's Saltire has also been linked to him.[1] Some authors have stated, however, that Patrick is not entitled to have a cross as a symbol since he was not a martyr, unlike Saints George and Andrew.[2]

Celtic Cross

[edit]

It is popularly believed that St. Patrick introduced the Celtic Cross in Ireland, during his conversion of the provincial kings from paganism to Christianity. St Patrick is said to have taken the symbol of the sun and extended one of the lengths to form a melding of the Christian Cross and the sun.[3]

Saltire

[edit]

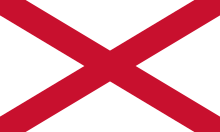

Saint Patrick's Saltire is a red saltire on a white field. It is used in the insignia of the Order of Saint Patrick, established in 1783,[4] and after the Acts of Union 1800 it was combined with the Saint George's Cross of England and the Saint Andrew's Cross of Scotland to form the Union Flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. A saltire was intermittently used as a symbol of Ireland from the seventeenth century, but without reference to Saint Patrick.

The Pepys Library's collection of broadside ballads includes one from c. 1690 called "Teague and Sawney: or The Unfortunate Success of a Dear-Joys Devotion by St. Patrick's Cross. Being Transform'd into the Deel's Whirlegig." It describes an Irishman (Teague) and Scot (Sawney), both stereotypically blockheaded, encountering a windmill for the first time and arguing over whether it is Saint Andrew's Cross or Saint Patrick's Cross.[5]

Cross pattée

[edit]

Some of the Order of St Patrick's symbols were borrowed from the pre-existing Friendly Brothers of St Patrick, including the motto Quis separabit?;[4] however, the "Saint Patrick's Cross" used in the Friendly Brothers' badge was not a saltire.[6] A 1783 letter to a Dublin newspaper criticising the Order's use of a saltire, asserted that "The Cross generally used on St Patrick's day, by Irishmen, is the Cross-Patee".[6] Whereas Vincent Morley in 1999 characterised the Friendly Brothers' cross as a cross pattée, the Brothers' medallist in 2003 said that the shape varied somewhat, often approximating a Maltese Cross.[6] Varying illustrations of the badge figure in the Brothers' 1763 statute book,[6] a 1786 letter to The Gentleman's Magazine,[7] and a 2008 photograph.[8]

Though both pattée and Patrick begin with pat-, the words are unrelated.[9][10]

Or a Cross Gules

[edit]Henry Gough in 1893 noted that Ireland was represented by a harp in the flags of the Protectorate, but at Oliver Cromwell's funeral the national banners had crosses, Ireland's being a red cross on a gold field.[11] Gough guesses Edward Bysshe may have co-opted the de Burgh Earl of Ulster arms for the purpose.[11] Gough suggests it gained currency in subsequent decades; it was called Patrick's Cross and shown alongside those of George and Andrew in various documents, including a 1697 drawing of William III, and The Irish Compendium of 1722.[11] A 1679 pamphlet account of heraldry states that the arms borne in the Crusades by the Irish Nation were "a red Cross in a yellow Field".[12] In 1688, Randle Holme explicitly calls this (Or a Cross Gules) "St. Patrick's Cross"[13] "for Ireland".[14] The County Galway unit of the Irish Volunteers in 1914 adopted a similar banner because "it was used as the Irish flag in Cromwell's time".[15] The flag used by the King's Own Regiment in the Kingdom of Ireland, established in 1653, was a red saltire on a "taffey" yellow background. The origins of the regimental colours remain a mystery however.[16]

Other heraldic designs

[edit]

In 1593–94, Irish Catholics in Habsburg Spain made unrealised plans for a "military order of Saint Patrick" to fight in the Nine Years' War, whose knights would wear a cross moline badge.[17]

A 1935 article states that during the Confederation, "the true St. Patrick's Cross was carried as a square flag: a white cross on a green ground, with a red circle."[18]

Monuments

[edit]Ancient high crosses called "Saint Patrick's cross" existed at places with legendary associations with the saint: the Rock of Cashel, where he baptised Óengus mac Nad Froích, King of Munster.[19] and Station Island, site of Saint Patrick's Purgatory, in Lough Derg, County Donegal.[20] Until the 18th century there was a "St Patrick's Cross" in Liverpool, marking the spot where he supposedly preached before starting his mission to Ireland.[21][22][23][24]

The arms of Ballina, County Mayo, adopted in 1970, include an image of "St Patrick's cross" carved on a rock in Leigue cemetery, said to date from Patrick's visit there in AD 441.[25]

Saint Patrick's Day badges

[edit]

It was formerly a common custom to wear a cross made of paper or ribbon on St Patrick's Day. Surviving examples of such badges come in a variety of colours[26] and they were worn upright rather than as saltires.[1]

The second part of Richard Johnson's Seven Champions of Christendom (1608) concludes its fanciful account of St Patrick with, "the Irishmen as well in England as in that Country, do as yet in Honour of his Name, keep one day in the Year Festival, wearing upon their Hats each of them a Cross of red Silk, in Token of his many Adventures, under the Christian Cross".[27] Irish soldiers stationed in Britain in 1628 reportedly wore red crosses on Patrick's Day "after their country manner".[26]

Thomas Dinely, an English traveller in Ireland in 1681, remarked that "the Irish of all stations and condicõns were crosses in their hatts, some of pins, some of green ribbon."[28] Jonathan Swift, writing to "Stella" of Saint Patrick's Day 1713, said "the Mall was so full of crosses that I thought all the world was Irish".[29] The crosses were also associated with Irish regiments, who were reported in 1682 to have been seen wearing crosses of red ribbon on St Patrick's Day; and with the English court, who were said to have worn crosses in honour of St Patrick on the saint's day in 1726.[30] In the 1740s, the badges pinned were multicoloured interlaced fabric.[31] In the 1820s, they were only worn by children, with simple multicoloured daisy patterns.[31][32] In the 1890s, they were almost extinct, and a simple green Greek cross inscribed in a circle of paper (similar to the Ballina crest pictured).[33] The Irish Times in 1935 reported they were still sold in poorer parts of Dublin, but fewer than those of previous years "some in velvet or embroidered silk or poplin, with the gold paper cross entwined with shamrocks and ribbons".[34]

Others

[edit]On the St. Patrick halfpenny, Patrick is depicted holding a crozier headed with a patriarchal cross.

The badge of the Companions of Saint Patrick, a nonpartisan but mainly unionist group of Dublin civic leaders active from 1906 until the 1930s, featured a red Celtic cross on a white background.[35]

Further reading

[edit]- Hayes-McCoy, Gerard Anthony (1979). Pádraig Ó Snodaigh (ed.). A history of Irish flags from earliest times. Dublin: Academy Press. ISBN 0-906187-01-X.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Morley, Vincent (27 September 2007). "St. Patrick's Cross". Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Hayes-McCoy, p.38

- ^ "The History and Symbolism of the Celtic Cross – Irish Fireside Travel and Culture".

- ^ a b Galloway, Peter (March 1999). The most illustrious order: the Order of St Patrick and its knights. Unicorn. pp. 171–2. ISBN 978-0-906290-23-1. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "Teague and Sawney". English Broadside Ballad Archive at University of California, Santa Barbara.

- ^ a b c d "Ireland: St Patrick's Cross". Flags of the World. 6 June 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Nibblett, Stephen (April 1786). "Letter". The Gentleman's Magazine. 56 (4): 297, fig.4 & 298.

- ^ Dennis, Victoria Solt (2008-03-04). Discovering Friendly and Fraternal Societies: Their Badges and Regalia. Osprey Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7478-0628-8. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ "pattée, adj.". Oxford English Dictionary. June 2005. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

< Anglo-Norman patee and Middle French patée, pattée ... feminine of patté pawed ... < patte [paw]

- ^ Hanks, Patrick; Hardcastle, Kate; Hodges, Flavia (2006). "Patrick". A Dictionary of First Names (online 2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-172667-5.

his name appears as Patricius 'patrician' (i.e. belonging to the Roman senatorial or noble class), but this may actually represent a Latinized form of some lost Celtic (British) name.

- ^ a b c Gough, Henry (1883). Marshall, George W. (ed.). "St. Patrick's Cross". The Genealogist. VII. London: George Bell and Sons: 129–131. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ^ Morgan, Silvanus (1679). Heraldry epitomiz'd and its reason essay'd. London: William Bromwich.

- ^ Holme, Randle (1688). The academy of armory. Chester. An Alphabeticall Table, s.v. "C"; Chap.5, p.2.

- ^ Holme, Chap.5, p.2

- ^ Hayes-McCoy, p.200

- ^ "History Reconsidered".

- ^ Walsh, Micheline (1979). "The Military Order of Saint Patrick, 1593". Seanchas Ardmhacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society. 9 (2). Armagh Diocesan Historical Society: 274–285. doi:10.2307/29740927. JSTOR 29740927.

- ^

a special correspondent (1 Jul 1935). "The city of the Confederation: the great moment in Kilkenny's history". The Irish Times. p. 3.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Jones, R; John Mason (2006). Myths and Legends of Britain and Ireland. New Holland. p. 123. ISBN 1-84537-594-7.

- ^ O'Connor, Daniel (2009) [1879]. Lough Derg and Its Pilgrimages: with map and illustrations. BiblioBazaar, LLC. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-103-18445-3.

- ^ Saint Patrick's Cross Liverpool

- ^ Hughes, James (1910). Liverpool. Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ Burke, Thomas (2008) [1910]. Catholic History of Liverpool. Read Books. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4086-4250-4.

- ^ McMahon, Vincent. "History Around You: Crests and Coats of Arms". History Around You. Teachnet. Archived from the original on 2003-09-09. Retrieved 2009-07-13.

- ^

"New coat of arms". The Irish Times. 14 January 1970. p. 8.

Ballina Urban Council has officially approved a design of two pikes representing the '98 Rising, St Patrick's Cross, a salmon and a ship depicting commerce and trade.

- ^ a b Hayes-McCoy, p.40

- ^ Johnson, Richard (1740). "Of the Praise-worthy Death of St. Patrick ; how he buried himself : And for what Cause the Irishmen to this Day, do wear their Red Cross upon St. Patrick's Day.". The renowned history of the seven champions of Christendom; St. George of England, St. Denis of France, St. James of Spain, St. Anthony of Italy, St. Andrew of Scotland, St. Patrick of Ireland, and St. David of Wales. London. p. 193.

- ^ Colgan, Nathaniel (1896). "The Shamrock in Literature: a critical chronology". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 26. Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland: 349.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (2008). "Letter 61". Journal to Stella. eBooks@Adelaide. University of Adelaide. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- ^ Nelson, Charles (1991). Shamrock. Kilkenny: Boethius. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-86314-200-1.

- ^ a b The popular songs of Ireland, pp.7-9 collected and ed., with intr. and notes, By Thomas Crofton Croker Published 1839

- ^ Atkinson, George M. (1887). "Description of Antiquities under the Conservation of the Board of Public Works, Ireland". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 18: 251, referencing plate facing p.249. Retrieved 21 August 2015.

I put on the plate a form (fig. 4) that I have often seen. Some thirty years ago it was very generally used in the South of Ireland on the 17th of March, and called "St. Patrick's Cross;" it was cut out of paper, and pinned to the cap of boys and on the right shoulder of girls. Many times have I seen a small cut branch of a tree doing duty for a pair of compasses to strike out the form, which was about four inches in diameter, and proud was the boy who possessed a box of paints, enabling him to fill in the forms.

- ^ Colgan, p.351, fn.2

- ^ "Irishman's Diary: The Patrick's Cross". The Irish Times. 13 March 1935. p. 4.

- ^ Findlater, Alex (2013). "6. A Southern Unionist Businessman: Adam Findlater (1855–1911)". Findlaters: the story of a Dublin merchant family, 1774–2001. A. & A. Farmar. ISBN 978-1-899047-69-7. Retrieved 7 June 2020.; "Lot 158: Circa 1935 Companions of Saint Patrick and 1936 Edward VIII Empire Day medals". The Eclectic Collector. Whyte's Auctions. 3 February 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2020.